We talked to history professor Serkan Yazıcı about his new book, Sultanın Saatçisi (The Watchmaker of Sultan).

Through Sultanın Saatçisi , Serkan Yazıcı says that he wrote the history of Turkey starting from 1878, yet this time he wrote the book by looking at the history of flowing behind the window of a watchmaker’s store in Karaköy. Johann Meyer, the first owner of this shop in Karaköy, is a German watchmaker who received engagements from Sultan Abdülhamid with the Hamidiye Watch he designed. The story of this watchmaker, founded by Johann Meyer, continued with Emil and Wolfgang Meyer, the second and third generation representatives of the family, until 1982. With the story of the Meyer family spanning over a century, a door opens to our recent history from the watch dials.

How was your journey until Sultanın Saatçisi ?

I have been in academic life since the 2000s, and I continue my studies in the field of Contemporary History at Sinop University. My doctoral thesis is “The Process of Institutionalization of Political Opposition in the Ottoman Empire”. To date, before Sultanın Saatçisi , we compiled the stories of 25-hundred-year-old brands with a study called Century-old Stories with the Century Brands Association. Sultanın Saatçisi , on the other hand, was a book on the shelves of bookstores, unlike my previous institutional history works. From the very beginning, we wanted this story not to be limited to the world of watches, but to meet the reader.

“I found myself rewriting the last hundred years of Turkish history, but looking through the window of a watch shop in Karaköy.”

The meeting of this story with the reader gains importance as it also witnesses the three-generation story of the Meyer Family, the history of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey…

This century-old story is the story of three members of the Meyer family, starting in 1876 and ending in 1980. A family that has witnessed a great historical process. I said this in the preface of the book, I found myself rewriting the last hundred years of Turkey’s history, but by looking through the window of a watch store. This watchmaker’s store in Karaköy was once in the center of both the Ottoman Empire and the Republic, in the city where all the changes took place. Of course, a family from Turkey is affected by all the changes brought by the years, but here is a German family. A hundred-year-old guest family living with a residence permit. During this guest life, they were deprived of many rights that a state would offer to its citizens. So, a family that has seen more than we have seen in a century. After the First and Second World Wars, they went through periods where they did not know where they would go, almost like Haymatlos. After Germany was defeated in the Second World War, Turkey wants the Germans in the country to return to their homes. Germans who do not want to return are placed in various cities of Anatolia, such as Kırşehir, Yozgat and Çorum, with an application called internment. They also witnessed the lowest points in the history of Türkiye. During the Ottoman period, the Medal of Honor and the Medal of Honor were awarded to Johann Meyer, and Emil Meyer had a conversation with Atatürk. A family that has seen both the peaks and all the difficulties of the century.

“Emil Meyer’s daughter says she was a German with a Turkish mentality when describing her father.”

How did the years of exile affect the Meyer family?

There are times when they are difficult. Since Germany was defeated in the First World War, the economic activities of the Germans are restricted; Probably Meyer’s shop was also closed between 1918-21. Emil Meyer also goes to Germany and works there. In fact, just at that time, Johann Meyer passes away and Emil Meyer tries to return to occupied Istanbul to keep his family afloat. If you will see it in the book, in the letter he wrote to the joint commission in Istanbul, he writes that he wants to return so that his family is not destroyed. The exile at the end of the Second World War was applied much more strictly. Germans from the same family were sent to different Anatolian cities; while Emil Meyer was in Çorum, Wolfgang Meyer was sent to Kırşehir. However, in this second exile, the shop in Karaköy is not closed, and even the watches that the masters in Karaköy cannot repair are sent to Kırşehir. By the way, this second exile is one where you can take a limited number of items and money with you and not do a job that earns money. That’s why, Meyers don’t do it for money when they fix local people’s watches, by the way. Wolfgang has a memoir that he talks about those days, when you look at the memories there, you see that he never complained. He was able to integrate with the Anatolian people, attended funerals, and sat at people’s tables. Emil Meyer’s daughter says she was a German with a Turkish mentality while describing her father.

Let’s come to the watchmaker side of the family; During the reign of Abdülhamid II, Johann Meyer produces the Hamidiye Clock. What kind of watch was the Hamidiye Time?

Let’s look at the period first. There was a life with two watches that showed both Turkish and European time, and in these years, watchmakers were developing certain dials and mechanisms in their own way and making additions to them. This is what Johann Meyer does, in fact, he is developing a mechanism that will display both Turkish and European time on a single dial. The spinning wheels are connected to different fractions, making it possible to display both times accurately and simultaneously. Before Meyer, watches were produced that could display two times together, but there were watches that needed to be adjusted every day, the model produced by Meyer required adjustments at longer intervals, approximately every two to three weeks. He develops this a little further and turns it into the watch he calls the Hamidiye Clock in the 1890s. The first produced Ezan Clock is a prototype, and the Hamidiye Clock is a watch that is a candidate for further commercialization. II. He was awarded by Abdülhamid first with the Order of Majidi and then with the Medal of Honor.

“Johann Meyer also places the clock on the sea face of the clock tower in Dolmabahçe Palace.”

Johann Meyer places the clock on the sea face of the clock tower in Dolmabahçe Palace. There are clocks on all four sides of the tower, and a mechanism in the middle. Each watch dial on the four faces is connected to this mechanism. The clocks in the tower are not Meyer clocks, but the installation belongs to Meyer. However, it was possible to see Meyer watches in many parts of the city in those years; squares, stations, factories…

Do you know any famous names that watches repaired by Meyer family?

Meyer’s workplace is very close to the places where Atatürk spend time in Karaköy during his youth. Therefore, we guess that Atatürk stopped by. On the one hand, it is known that he met with Emil Meyer during his days at the Dolmabahçe Palace. Kazım Taşkent, the founder of Yapı Kredi, and İlber Ortaylı visit Meyer on various occasions. Rahmi Koç and Erdal İnönü are also among their customers. And also, many academicians who are interested in watches and physics become customers of Meyer, Muammer Dizer is one of them. It seems to me that especially Emil and Wolfgang Meyer have more of a public relationship.

The Meyers keep records of nearly all of their customers. Are the archives there?

The recording issue is really important to the Meyers. There is Ursula Karaokçu and another gentleman, who is solely responsible for keeping records of customers. These notebooks are not currently in the archives of the Meyer company, as far as I know, they are in one of Wolfgang Meyer’s masters, Recep Gürgen. Wolfgang opens a separate office for Gürgen to repair more special watches. As far as I know in the notebooks, he stays in this office, Mr. Recep.

“This watch store that in Karaköy was much more than an ordinary watchmaker.”

What do you think is the place of Meyers in Turkish watchmaking?

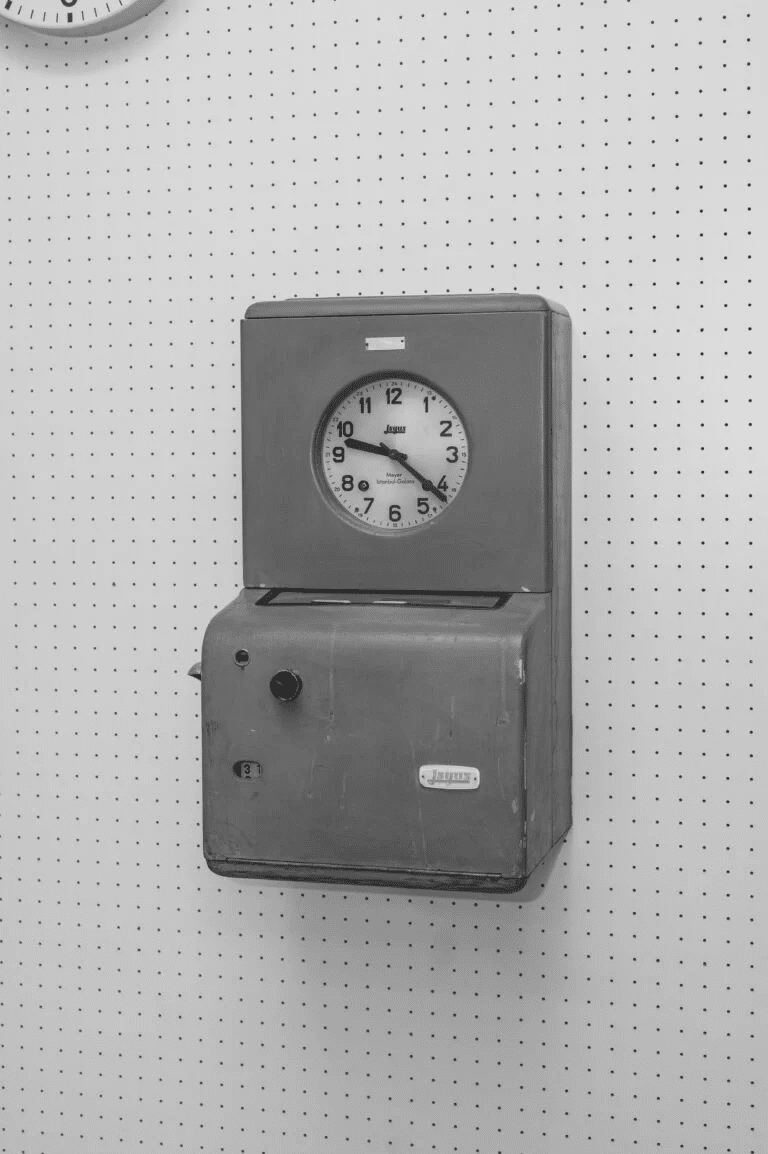

Meyers is a family that brings us together with many watch technologies, both in terms of industry and daily time. Clocks are seen as the footsteps of the technological revolution. Adapting to industrial life and business forms is through time tools where we can control them. The entrepreneurial side of Meyers also meets this need in our land. And of course, there are the watchmakers who grew up with them. Önder Şamhal is still one of the watchmakers working within the body of Meyer. Mr. Recep, whom we have just mentioned, is one of the masters that Wolfgang trained. And these craftsmen were able to repair all clocks, not just Meyer clocks, because the Meyers also repaired wall clocks, industrial clocks, and guard clocks. Therefore, this watchmaker’s shop in Karaköy was much more than an ordinary watchmaker.

Will there be a study on the Meyer archives?

Today’s owners of Meyer Objects, Nahsen Bayındır, have both watches and some materials about the company in their office in Ümraniye. Onur Bayındır also has many materials. Currently planning a museum work, Meyer Objects will become a fine watch collection and Meyer Museum. It looks like it will be a very interesting collection such as envelopes, invoices, letterheads, Meyer branded wallets.

The seeing eye can grasp that this is not just the story of a family. You can read the story of Turkey once again from the story of the Meyer family. It is even possible to see periods and moments that you cannot see in a political history book. Perhaps it was not always possible to see from a historical text about the Second World War that a limited German community was interned in Anatolia. That’s why, Sultanın Saatçisi is, on the one hand, a social history study.

So, how did the Sultanın Saatçisi come about?

It was a mature idea before I got involved. They thought this story would make sense if told well, as Meyer’s current owners have a serious archive resource. Somehow, he contacted me. I examined both the material in Meyer’s hand and scanned the Ottoman archives. If the story of an institution is reflected in the state archives, it is also reflected in the literature and press collections. It definitely finds a response in various memoirs or literary works. I really enjoyed seeing all these. There is a time when Emil Meyer went abroad to work, during the First World War. After the death of his father, Johann Meyer, he wants to return to keep the company and his family afloat. The first thing I read was this petition that Emil Meyer wrote to get back. It was very touching to me. I like to get into the story when it touches me, it makes sense to me. Wolfgang’s memories also motivated me a lot.

How long did it take to write the book?

We were planning to finish it in a year, but it’s been two years. Our personal ups and downs were also effective in this. It was a one-year research process, and we worked with Akın Öge during this process. We carried out the research with Öge, and I wrote the text.

How did the time pass while you were writing the book?

Time flies fast when you’re experiencing something good, and so did when I was writing the book. I progressed chapter by chapter, I collected, I created in my mind and then I wrote the chapter. I can say it’s over in four breaths. First, we wanted to have a general narrative about time and hours, because there is something missing in the literature in Turkey. It is very valuable work, but very little. There is not much in Turkish. We added that part to the beginning of the book with the desire to cover that part a little bit. We wrapped up this century-old story by focusing on the story of each Meyer member. Of course, there were moments when the cursor got stuck. For example, I thought that it would be more appropriate to start talking about Wolfgang, for example, because Wolfgang’s story with his father is more complex.

“The mechanism that turns the hour and minute hands is the inspiration for the machines that emerged in industrialization.”

As a historian, how do you think the concept of time has evolved over the centuries in human life?

There are some fundamental factors that affect our understanding of time, related to how we look at it. When we look at it from the perspective of work and time, we relate to the clock differently when we look at it from the perspective of religion. The capitalist transformation has strengthened our bond with time, for example, the early people, in the West or the East, did not need a watch in their daily life. The light level outside is sufficient for people engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. But sailing wasn’t like that, so they used hourglasses. In geographies that cannot benefit from the sun, clocks such as hourglasses and water clocks are used to measure time. There is even a milk clock used by the Egyptian King Osiris. Actually, this is a model of the water clock, but Osiris powered the mechanism with milk. Another interesting example is the spice clock used by the French nobility to determine what time it is at night. There is a different spice in each watch chamber, they measure the time from the taste of the spice, without the need for light.

If we look at the cultures, since the West was included in the capitalist universe earlier and capitalism was shaped in the West, the relationship with the modern clock developed early there. We think that the development of the clock mechanism has also greatly influenced the development of the industry. In the process of factoryization and mechanization, much has been learned from the watch. The clock is actually an automaton, a robotic tool that displays the time. The mechanism that turns the hour and minute hands is a great source of inspiration for the machines that emerged in industrialization. So, the West got involved earlier and more firmly in this relationship. In the East, it was a little slower. It is a little bit of capitalism that shapes the relationship over time. Let’s think about today, minute by minute how much time we depend. More than ever, perhaps. Although the use of wristwatches seems to have decreased, we keep a close eye on time in different ways.

“I can say that the most painless revolutionary movement in the Republican revolutions was the hour.”

How was the use of watches in the last years of the Ottoman Empire and the first years of the Republic, in which we talked about the three generations of the Meyer family?

Since the 1910s, European clocks were already in widespread use, before the Republic, the European clock was switched. European watches were always used in government offices, stations, and ferries. Alaturka watch was a watch that was a little more related to daily life. Maybe for this reason, I can say that the most painless revolutionary movement in the Republican reforms was the hour. We can think like this; Turkish style was a watch associated with the sun, but life began to change with the modernization of society. The European timepiece was more suitable for these new times, when life continued even after the sun went down. For this reason, it was not difficult to switch to the European watch, which is practically more useful. In my opinion, Sultan Abdulhamid is also happy that Johann Meyer has adapted the European style to Turkish style, because the Sultan also wants the society to adapt to this modern time style. Perhaps what the Sultan rewarded was Meyer’s combination of the modern and the traditional.

There are types of watches that disappear over time, such as sheep and pocket watches. How do you think our relationship with the watch will continue?

It seems to me that wearing a wristwatch will belong to our generation. Generations after we, may not wear watches like we do. However, it is not possible for people to end their relationship with a device that will track time. Just as it evolved from a pocket watch to a wristwatch, we will still be tracking time in another way.